About a billion years ago, there was a high-powered bacterium — we’ll call her Mitey — who was skilled at redox chemistry. This is the same chemistry that runs batteries, and it’s much more energy intensive than the organic chemistry of life that came before. Mitey was a parasite who used her high-power chemistry to kill her host. And who were her hosts? One-celled creatures called archaea were the only other life forms at the time. Her host was named Archie.

Well, it wasn’t long (only a few million years) before Mitey learned the lesson that all parasites learn. If you kill your host, there’s nothing left to steal. Mitey learned to keep her high-power toxins to herself, to live and let live. She made her home inside Archie. She reproduced and had babies that also lived inside Archie. When Archie split in half to spawn little Archellas, some of the Mitellas went with each half.

And so Mitella’s fate came to be tied to Archella’s. And after only another few million years, some Mitellas had another idea. If they helped their Archella host, then Archella would do better, and Mitella would have more lebensraum. A win-win.

Every plant and animal in the world today is descended from Archie and Mitey.

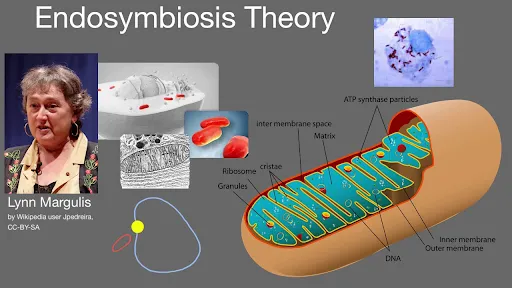

How to help Archella? One thing Mitella had in abundance was electrochemical energy. Mitella donated some of her prodigious energy to Archella. Archella learned to use it. The combination was unstoppable, and the rest is history. Every plant and animal in the world is descended from Archie and Mitey. Every cell in your body is filled with little Mitellas, and the cells are utterly dependent on Mitellas for the energy that powers their metabolism.

Today, we call them mitochondria. There are hundreds in every cell, thousands in the muscle and nerve cells that need more energy. Mitochondria have succeeded far beyond any range that was available when they were parasites.

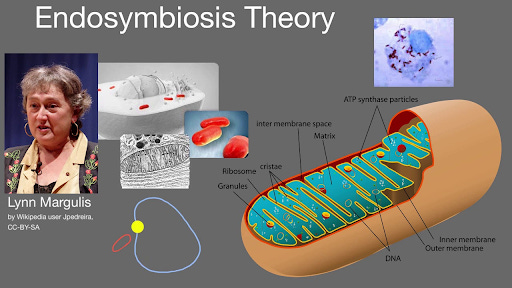

Lynn Margulis coined the word endosymbiosis for a symbiotic relationship within a single cell. She told this story in 1966 when she was still a grad student, and about 20 journals refused to publish her theory. Too radical. She finally succeeded with the Journal of Theoretical Biology, and today her theory is textbook biology, too commonplace to be associated with her name or her story.

Humans might learn a lesson from Mitey

Today, humans are a parasite on the planet, poisoning whole ecosystems, treating nature as a resource we can exploit. Parasitism is the first step toward symbiosis. We are beginning to learn from the damage we have caused, as it blows back to degrade our comfortable lifestyles. Some of us are poisoned by the same chemistry that is poisoning so many life forms on our lovely planet. We can hardly be surprised.

We have a feisty (if hamstrung) environmental movement, fighting the capitalist mindset, hoping to curtail some of our most destructive behaviors.

Human destiny

Cutting back on the poisoning and the habitat destruction is our present struggle. It is the limit of our vision. But it is not our destiny. Our destiny is to learn from the mitochondria.

There is some evidence — and I choose to believe — that the reason that America before Columbus was home to the richest ecosystems in the world was not because the First Peoples were too stupid to exploit the biosphere the way peoples of Europe and Asia were doing at the time. I choose to believe that the First Peoples’ ethos was different. They saw their role not as parasites on the land, but as symbionts. They knew how to use fire to maintain vast grasslands for herds of bison and elk. They knew how to plant gardens with adjacent flowers and vegetables that helped one another to grow. They planned seven generations in advance, and they planted their forests with fruits and tree nuts in the right combinations, mixed in with other deciduous and evergreen trees to make a vibrant, healthy forest. The forests they planted were richer and more productive than any in Europe or Asia, and I choose to believe that this was the product of a wisdom tradition.

So this shall be our destiny. We shall combine the First Peoples’ ethos with the methods of modern science. Under the stewardship of Future Human, Gaia will thrive and diversify and flourish as never before. The earth will be a richer, more beautiful environment than anything we can imagine, and far more productive for human needs than our technology of monoculture and fertilizer and toxins could ever achieve.

We shall tie our destiny to Gaia’s, and together we shall flourish beyond our most fantastic dreams. This is my prayer.

Footnote: Sometimes, a cell will commit suicide, destroy itself for the sake of the larger organism. In our bodies, cells are doing this all the time when internal signals detect that they have become cancerous or when they are infected with a virus. The process of cell suicide is called apoptosis, and to this day the destruction is carried out by the mitochondria, not on their own initiative but on cue from the cell nucleus. The mechanism involves high-energy redox chemistry (ROS), recalling the origin of mitochondria a billion years in the past.

Despite not considering myself a religious person I recite a similar prayer like a meditation mantra. Not particularly confident it will keep humans from biting off the hand that feeds us (too many Robby Starbucks out there) but one can hope.