It’s been 25 years since astronomical data was reported that threw the Big Bang theory into turmoil. To patch up the standard model of the universe, astrophysicists were forced to introduce dark matter and dark energy as completely unknown, undetectable substances that dominate the dynamics of the universe. All of the stars and galaxies, the gas and dust and plasma, the quasars and black holes—everything that we see is just going along for the ride, 5% of the gravitating matter that dominates the universe’s evolution. Even for scientists who have devoted their careers to developing Big Bang theory, this is an uncomfortable situation.

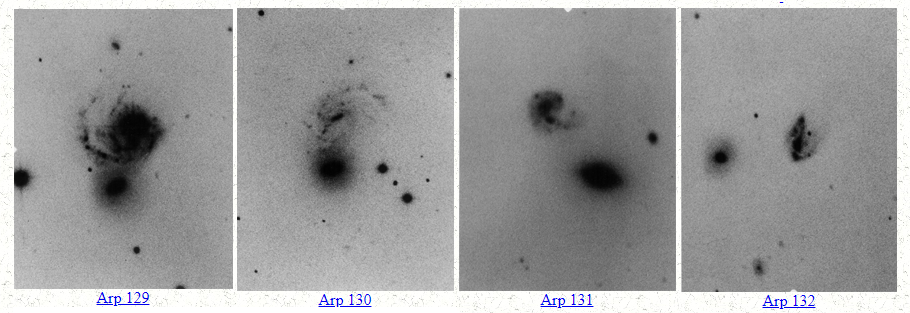

But 25 years before that, there was already a scientific gadfly with impeccable credentials who was warning that there were anomalies in the sky, observations that could not be squared with the assumptions that everyone was taking as foundational. This was Halton Arp. In 1966 he published his Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies. By 1978, he had established a connection that couldn’t be ignored between quasars (which are supposed to be the most distant objects in the universe, billions of light years away from us) and Seyfert galaxies, a class of ordinary galaxies that are supposed to be at least ten times closer to us.

In 1982, he showed that in almost all cases where a large galaxy had smaller companions, the smaller companion galaxies had higher redshift than the central galaxy. (If redshift comes only from velocity, why should all these companion galaxies be ejected in a direction that happened to be away from planet earth?) In 1984, the astronomy establishment shot the messenger. Arp was relieved of his post as director of Caltech’s Palomar Observatory, where Arp had been taking the pictures that showed the cosmology theorists that they had some explaining to do.

Arp then had to compete for telescope time with more mainstream projects; but until the end of his life (2013), he continued to collect thousands of cases of quasars that are not only close to galaxies in the sky but sometimes are (apparently?) connected to those galaxies by plumes of plasma. If a few quasars line up so they happen to appear in the same part of the sky as a nearby galaxy, that might be a coincidence. But with thousands of examples, it just didn’t make sense that these are all accidental alignments.

This is a radical challenge to a paradigm that has become entrenched over the last sixty years. How might we understand these anomalies? Arp is very clear that his primary message is observational: we need a new story. He offers one such story, but encourages others to make creative proposals; we shouldn’t confine ourselves either to the traditional story (redshift = distance) or to Arp’s suggested alternative.

Arp’s story begins with Ernst Mach, who put forward the idea in the 19th century that matter only obtains its mass in relation to other matter in the universe. Einstein cited Mach’s Principle as inspiration for his General Theory of Relativity.

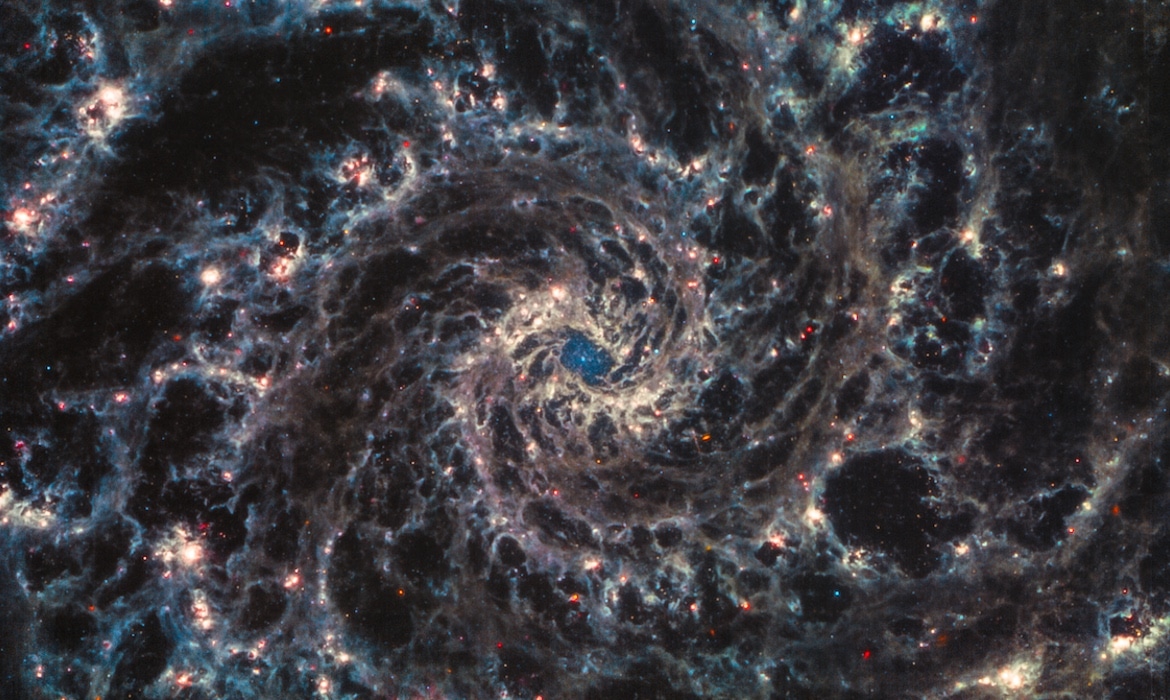

Arp proposed that matter is continually being created, but with zero mass, which grows as the new matter “becomes aware” of surrounding matter in the universe. There is not one Big Bang but many Little Bangs. Astronomers know of many “active galaxies” with black holes at the center that are spewing out matter. [Personal connection: my 1987 dissertation was about jets that emerge from black holes at the center of galaxies.] Conventionally, these jets are interpreted as matter that is sucked into a spinning black hole by gravity and some matter that doesn’t make it all the way in is shot out through the north and south poles. But in Arp’s interpretation, these are actually “white holes” and the jets are newly-created matter. A white hole is just a time-reversed version of a black hole, with matter coming out instead of falling in. There is nothing unphysical about a white hole.

In Arp’s world, a quasar is newly-created matter. It moves very fast because it has almost no mass, but gradually it slows down (conservation of momentum) as it gains in mass. So why do quasars have high redshifts? It is not because they are particularly far away, and not because they are moving away from us. Rather, it is because their electrons are new, and have not communicated with the whole universe yet. We just said that according to Mach, matter acquires its heft by relating to the rest of the universe. When electrons are new, they are not yet in touch with very much of the universe because of the finite speed of light. As the electrons become aware of more and more of the universe, they become heavier and heavier.

A (hypothetical) lighter electron produces just the same spectral lines as a redshift due to velocity.

Another thing Arp noticed was that redshifts of quasars were not continuously distributed, but tended to cluster around preferred values. He interpreted this as coming from the fact that a star first “notices” the nearest star, then the nearest cluster of stars, then its whole galaxy, then more and more galaxies. Each time that a new heavy object comes within a star’s horizon, the redshift of that star steps up; then the redshift stays at that value until the next mass structure comes within its horizon.

So, according to Arp’s model, the quasars are not fantastically bright and very far away; they are moderately bright and at the same distance as the galaxy that ejected them, and their redshift gets an extra boost from the facts that electrons are lighter when they are created, and gradually get heavier.

Quasars mature into galaxies over time. Our own galaxy presumably had its birth in one such event, and the mass of the electron that we observe in our local region of the universe reflects the age of our own galaxy. As we look further and further out into space, we see galaxies at an earlier and earlier time, because of the finite speed of light. So the galaxies we see tend to be younger, hence their electron mass is less than ours, hence they tend to be more redshifted the further we look back in time. This is Arp’s story, and I’m not sure it holds together. It seems not to be consistent with Fred Hoyle’s Steady State universe of the 1950s, because in Hoyle’s universe, looking back in time, the galaxies are not, on average, younger. That’s the meaning of “steady state”.